Intersectionality, coined in 1989 by legal historian Kimberlé Crenshaw, highlights the fact that the many factors of being human, including race, gender, and religion, overlap in important ways. These points of overlap, or intersection, are often positions of oppression. Think of race and gender. In American society, the position of power in race is whiteness and in gender is male. In comparison, a non-white woman is subjected to oppressive forces in society. Thinking about intersectionality helps reframe issues bringing the oppressed toward the center, rather than multiply marginalized. Ideally, intersectionality allows for stronger analysis of complications. In other words, intersectionality helps everyone be included particularly those who are oppressed and excluded.

So, what does this have to do with museums? Many articulate people have written about this including Gretchen Jennings and Porchia Moore, Nikhil Trivedi and Porchia Moore, Andriel Luis, and Seph Rodney about the AAM conference. In this post, I share my meaning-making efforts on the topic.

What do new voices have to do with Intersectionality?

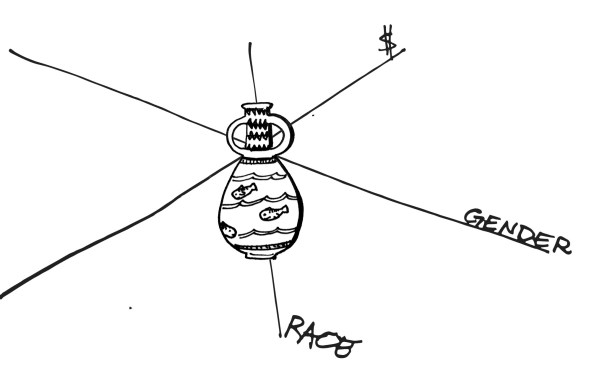

Think of this artwork. We do use many facets to consider this object; think of all the fields in a database. However, most institutions keep data based on curatorial research, i.e. filtered through an academic lens. Some institutions, like history museums, include oral history to add additional layers of information. But most fields do not. This vase, if it were in an art museum, might be described by media and style. In a history museum, it might be seen as an artifact of an ancient society. In other words, our academic specialties already segregate layers of meaning.

Even beyond that, most museums don’t have database fields to fill in about how this artwork might be seen through a lens of class, race, or gender. These issues are often discussed in chat labels for modern and contemporary artworks, but gender, race, and class have been in play since humans started flaking flints, I wager. Why is this important? First, from an academic perspective, we are missing meaning-making opportunities. But, also, we are not doing the foundational work in thinking more broadly about our collections.

Visitors need points of connections to our collections. Before the accusations of pandering are launched, I am not advocating for removing media, style, period, or any other traditional field of interpretation. Instead, intersectionality allows museums to add to their strong interpretation skills. Plenty of meaning about collections is hidden ready to be uncovered by re-viewing the interpretation.

But what does this mean practically?

Look at galleries. How are they segmented? Are the “women artists” the only ones where labels discuss gender? Where are “black artists” placed? What about your staff? Do you tout your black educator as a point of diversity? Your first Asian curator?

Basically, step back and be more purposeful in your actions and words. Give it a mental 360 in terms of how you might be handling issues of race, gender, class, religion… Get help on your thinking. Bring in new voices to help you.

Let’s go back to that vase. Any sense of who made it? Was it a woman? Was it for a rich person? Was it made by slaves? Was the archaeological site in a politically contested area? Were there human remains there? Any of these questions make you a little uncomfortable? I bet. They make me uncomfortable. Many of them touch on the unsaid verboten topics of art and history museums. But, when we don’t answer these questions for ourselves, and for our visitors, we are hiding parts of an object’s history.

Challenges in Including New Voices

Museums professionals often work in synthesizing and organizing information, distilling all along. This is often work that is easier done alone. More people would make the work of research take longer. Time is of the essence in museums. A new exhibition opens scantly 6 weeks after the last with all the requisite work to make that happen. Anything that slows that down feels onerous and frightening. But, what if that time was planned in at the beginning? Once you get efficient at adding people, this time and work will seem doable.

New voices bring with them new ideas. Those additional voices might say things that you don’t want to hear. What if they share their dislike of your institution? They might call out your faults like your institutional racism. Well, yes, they will probably share your faults. But, you will never improve if you don’t know what to improve. And, they might completely hate museums, but this is fairly unlikely. People will likely not spend time sharing their time with you if they inherently dislike you. If they truly hate you, they might be moved by strong emotion to tell you. But, once the conversation is done, that moment of discomfort is over.

What needs to change?

Intersectionality has had some important lobs launched at it. Firstly, it seems like the word du jour, no different than diversity other than the spelling. This is fair claim, in my mind. It is jargon. People use intersectionality in uninformed ways to suggest their own “wokeness”. Yet, these words exist because as a culture we are trying to communicate ideas of equity. If these words help more people act better, then I am all for them. At its essence, intersectionality is about bringing more into the conversation for greater, more fair, meaning-making. More meaning means connecting to more people.

Museums are actually about intersectionality. They bring together disparate ideas into spaces for people to make meaning. They invite people to interface with complicated ideas. However, museum’s idea of intersectionality are often neutralized, devoid of the factors that particularly oppress people. Adding these lenses would be in keeping with the method of museums and bring museums closer to accomplishing their mission to understand collections wholly.

Basically, museum professionals, across the hierarchy, need to want to change. Then, they need to seek out training. Thinking about collections this ways is almost like being asked to see the invisible friend that has been in the room all the time. Just as Big Bird finally got the folks on Sesame Street to see the Snuffleupagus, trainers can help staff see the elephants in your galleries. What happens when you see the elephant? Will it be a circus? Maybe. Or maybe, it will be a fantasia of meaning-making full of visitors.