In museum galleries, we signal ideas through a variety of ways. Collections are visible in the galleries. Interpretation adds more signals, like ancillary images, audiotours, and of course text. But, we also omit many stimuli. We often completely exclude two major forms of meaning-making, kinesthetic and tactile. What happens when we do this? And, what are ways that we can foster these senses?

Meaning-Making

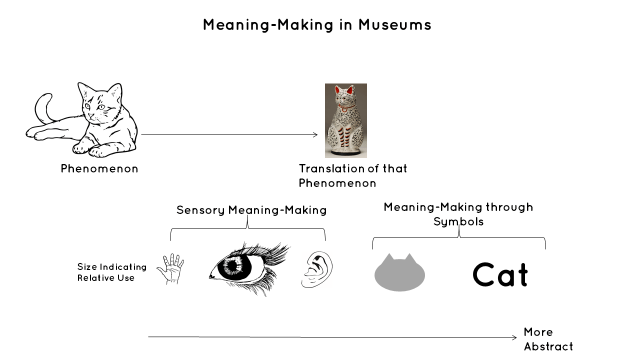

Every moment of the day, awake or not, we make take in sensory information and make sense of the world. Some stimula are fairly direct. We smell a musty odor and match that to a memory of skunk smells. Other times, we receive information that has been translated by an individual (like you are reading about skunk smell now).

Most objects in museums are translations of phenomena. Fossils were once a living, breathing creature. Artworks might relate a concept, idea, or experience. Look at the example above. An artist has created an image of a cat. Now, in understanding that object, you can use your senses. In museums, you will most likely not be able to touch it. You could listen to an audiotour, but you couldn’t be able to hear the sounds of striking it (ping) or dropping it (crash). Most likely you will need to use vision as your primary sense, either through looking at the object or reading the text (a translation of the object into text that the reader must interpret.)

Touch

In other words, in the vast majority of museum settings, visitors must rely on the mediation of the museum interpretation. They need to use visual sense as the primary source whereas in the rest of the world they use many more sources of information.

Humans have a distinct haptic system, where they use touch to reflexively seek and acquire information, even more quickly than with the sense of sight. Many types of information are most easily ascertained through touch like hardness, temperature, pliability, weight. These topics can be learned through verbal communication, yet they are more easily ascertained if you just reach out your hand. People often act on this need to understand through touch before their rational senses take hold.

Touch can evoke memories but also quickly immerse people in new experiences.Touch is a type of learning that is often fostered in early childhood. Engaging in learning through touch is pleasurable.

Kinesthetics

Touch is not the only sense that people lose in the museum. Spatial and kinesthetic sensibilities are often challenging. Works are seen out of context. While the fossils of some dinosaurs are seen in its full forms, many bones might be framed in a case. Because of that, you can’t walk around the whole creature. You can’t understand your relative scale to this animal, for example.

Kinesthetic experiences allow learners to connect actions to ideas to develop deeper understandings of concepts and developing critical thinking efficiently. This connection of body and mind is called embodied learning, in which abstract ideas are made more salient when connected to concrete physical action. While kinesthetic learning is so important for meaning-making, this form of engagement is underrepresented throughout the educational ecosystem.

Kinesthetic learning has some important ancillary benefits. Experiences that foster learning through actions usually have a flexibility that encourages creativity, experimentation and problem-solving. The sheer act of moving put learners in a position to see spaces and objects from a new perspective. In museums, ideally, kinesthetic learning should feel authentic and meaningful. And, kinesthetic learning also encourages collaborative action.

Authenticity

Streamlining to visual senses have major problems for visitors. Spatial and tactile learning can certainly help those with hearing and sight impairments, but these types of experiences empower everyone making collections more memorable for all. Together these senses can evoke emotions and encourage fascination.

The challenge for museums is that touch and kinesthetic action are natural ways that humans make meaning. The sense of touch is the easiest way to ascertain authenticity, for example. People are well aware when an experience feels inauthentic. Museums need to be thoughtful, therefore, in the experiences they produce, for example, using high-quality replicas. When chosen appropriately, handling replicas or other materials can stimulate engagement.

Touch does not mean to wildly grab collections. Museums need to help visitors learn appropriate handling behaviors. Ideally, touch can be added into museum spaces without unleashing an avalanche of destruction. Reality-based interactions on tablets can offer some of the benefits as touching objects. While more research needs to be done, virtual touch does seem to be a real option.