Congratulations! You’re the new director of the art museum of New South Overthere. It’s a cash poor institution with a great collection of little known masters of underwater basket weaving, lantern slides, zeppelin models, and lamp glass. Your first few months are exhilarating but also exhausting. You make some missteps. Its natural. But, the key is learning from your failings. Read these five scenarios and test your knowledge of bias in the museum setting. For each, read the scenario and try to suss out where bias comes into play.

Scenario 1

We all know visitors hate contemporary art. But, your curator has been agitating for a main gallery show. The New York Times might even finally give you a review; I mean that is just like minting gold in terms of donor dollars. You give the curator the go ahead. Opening day rolls around, and no one comes. You are not surprised. You had spent a year’s worth of meetings being told no one would come. Everyone told you and you should have listened. But, it’s really just because the audience doesn’t get it. Right?

Explanation

Confirmation Bias is when you find that everything points to exactly what you thought. This is natural in the museum world; we are often surrounded by those trained in the same manner as ourselves. We are the people who visit museums for fun! Yet, what is happening here is a cognitive dissonance, or split between our thinking and the thinking of others. Basically, you are surrounding yourself with people like yourself, while ignoring other responses.

In the case of that contemporary exhibition, you wonder what other mitigating factors played into this situation. With the foregone conclusion that this would be a light attendance exhibition, they might not have produced a gangbusters marketing program. Also, did they frame the interpretation in an accessible manner? Or did they instead decide that this show would be for a specialist audience? In other words, did they propagate low attendance by starting with a certain assumption?

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Scenario 2

Its already budget time and you have to make the tough call. There is only $1000 in this year’s operating budget. So, every dollar counts. Frankly, every penny counts. What choice are you going to make? It’s all about having the newest thing. I mean museums are basically academic institutions. While it isn’t publish or perish, it definitely is about innovate or perish. You just read an article about just this issue that one of your executive team members pass on. You know that you need to be on the cutting edge to be the best. Your executive team keeps telling you this in meeting after meeting. With budget time rolling around, you need to either allocate money to innovation or to maintenance of the classrooms. You vacillate, but it seems pretty obvious. I mean you are totally in agreement with the executive team–innovation all the way.

Explanation

Now while this story shows a possible innovation bias, it also highlights the bias that can come from being too insular, the ingroup bias. In large institutions, this can occur particularly due to the hierarchy. But, even in small institutions, you might find yourself always turning to the same people. You are closing yourself off to other ideas; you naturally become biased to the things you have heard.

Before making this decision, you might speak to the people associated with both budget requests. You might also try to weigh the relative impact and need for both requests. In other words, you might try to gain information not filtered by your own ingroup before making your decision.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Scenario 3

After the last exhibition flopped, oh Contemporary Art, you want to be sure the next one will be both a popular and critical success. To this end, you direct your staff to do focus group after focus group to find out what the public is into. Your research team has suggested that you do fewer focus groups, but you are not going to be ill-prepared this time. You read the New York Times daily in hopes of finding out what is hot this year. You call around to other directors to see what is on their exhibition schedule. You are going to get it right this time.

Explanation

There can be a point where you have too much information. This bias, the information bias, is the belief that more information will result in a better decision. In this scenario, the director is compiling information without a concrete goal in mind.

Certainly, she wants more people at exhibitions. But, she isn’t actually acting in a truly goal-oriented way. A better goal might be find an exhibition that resonates with our members or find an exhibition that brings in new members. These are concrete goals that can then be considered researched and articulated. Instead, scattershot, she was just compiling information; and more information does not always mean a better decision.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Scenario 4

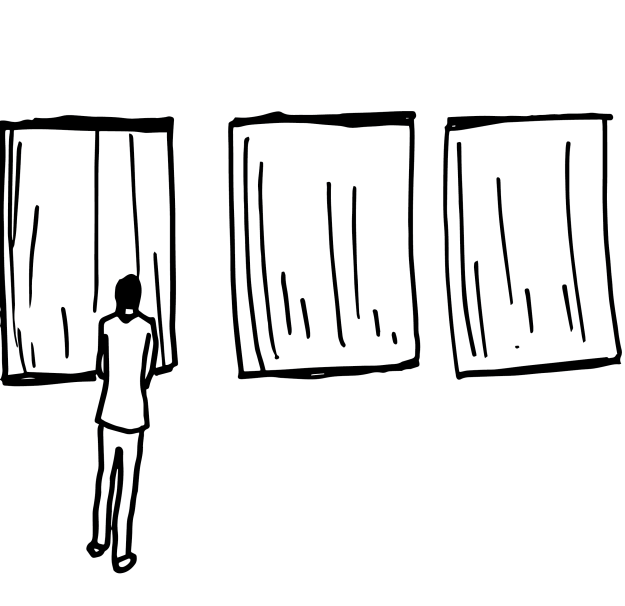

You decide that the galleries are looking a bit shabby and could use a fresh coat of paint. While the baskets are removed and placed in storage, the signage is taken down so that the walls can be painted. Before the galleries are reinstalled, the museum’s chief technology officer asks if the objects can be displayed slightly differently. All gallery text should be removed, the CTO suggests, because there is this wonderful museum app. The curator on the other hand has just come into your office. She is irate. There just have to be labels, she says. The curator threatens to leave if this change goes into effect. The director can’t possibly do without a curator and so the decision is to use labels.

Explanation

The team decided instead to stay with the old tried and true. This is an example of the conservatism bias. This is when a person favors older information over the new. The curator prefers labels stuck to the wall in front of the object than embrace new way of delivering the information.

The team could have decided to do a test comparison, using one section to test app only labels. After doing this test, the team would have more information at their disposal to help make their decision.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Scenario 5

This signage scuffle just will not go away. The curator is holding fast to the labels. The chief technology expert, emboldened by an article in the New York Times entitled “The Death of Labels”, is looking to rid the building of all its signage. The CTO has also read an article in Fast Company about Microsoft’s newest product, the wearable MicrosoftDance (MD) that generates a hologram that dances textual information. He knows this new technology will be idea to get people to finally love the museum’s lantern slides. Additionally, the public can use the MD not just for what is in the galleries but also wayfinding and information on upcoming events. You are not exactly sold, but you decide to move forward on the DanceLabels.

Explanation

The CTO’s belief that all the visitor-centered needs will be meet by this new digital tool is a clear example of Pro-Innovation Bias. This bias is the overvaluing of the usefulness of the latest technology while underestimating its limitations. Sure, MD sounds great to the CTO, and the prospect of museum patrons engaging with the collection or finding their way through the museum sounds cutting-edge (if terrifying to conservators). But will it truly meet the needs of all the visitors? Will it work in every instance?

In this case, one should again weigh multiple voices. A competitive analysis of other institutions might help, though if you want to be the first than you will not have the advantage of learning from other’s mistakes. Again, testing works well in innovation bias. Try the new solution against other solutions. So for example, test the efficacy of MD against static signage pointing the way to the cafe.